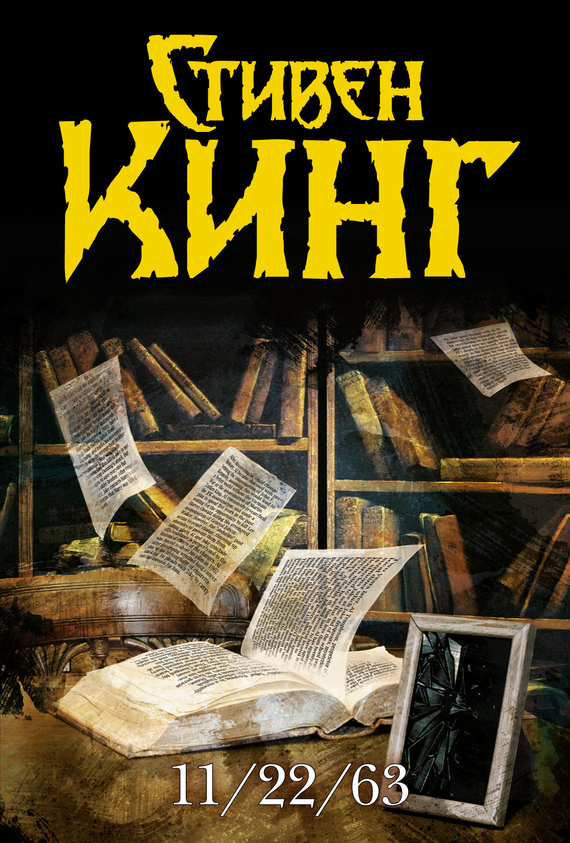

11/22/63 Кинг Стивен

Для влюбленных оспины – что ямочки на щеках.

Японская поговорка

Танец – это жизнь.

Пролог

Я не из плаксивых, никогда таким не был.

Моя бывшая говорила, что «отсутствие эмоциональной гибкости» – главная причина, по которой она ушла от меня (как будто парень, встреченный ею на собраниях АА, не в счет). По словам Кристи, она смогла бы простить меня за то, что я не плакал на похоронах ее отца: я знал его только шесть лет и не понимал, какой он удивительный, щедрый человек (к примеру, на окончание школы она получила кабриолет «мустанг»). Но потом я не плакал и на похоронах своих родителей – они ушли с промежутком в два года, отец умер от рака желудка, мать – от острого инфаркта миокарда, который случился, когда она прогуливалась по флоридскому берегу, – и тогда Кристи начала понимать, что у меня отсутствует вышеозначенная эмоциональная гибкость. По терминологии АА, я не «чувствовал своих чувств».

– Я никогда не видела тебя плачущим, – говорила Кристи тем бесстрастным тоном, к какому прибегают люди, когда доходит до окончательного, не подлежащего обсуждению разрыва. – Ты не плакал, даже когда сказал мне, что я должна пройти реабилитацию, а не то ты от меня уйдешь.

Разговор этот произошел примерно за шесть недель до того, как она собрала вещи и перевезла их на другой конец города, переехав к Мелу Томпсону. «Найди свою вторую половинку на собрании АА» – еще одна их крылатая фраза.

Я не плакал, когда смотрел, как она уходила. Не плакал и когда вернулся в маленький дом с большой закладной. Дом, в котором не появился ребенок и уже никогда не появится. Я просто лег на кровать, которая теперь принадлежала только мне, прикрыл рукой глаза и стал скорбеть.

Без слез.

Но никакого эмоционального блока у меня нет. В этом Кристи ошиблась. Однажды мама встретила меня, девятилетнего, у двери, когда я вернулся из школы, и сказала, что моего колли, Лохмача, сбил насмерть грузовик, а водитель даже не остановился. Я не плакал на похоронах Лохмача, хотя отец говорил, что никто не примет меня за слюнтяя, если я заплачу, но слезы потекли из глаз, когда мне сказали о гибели собаки. Отчасти – потому что я впервые столкнулся со смертью. В основном – потому что ответственность за гибель пса лежала на мне. Я не убедился, что Лохмач в полной безопасности и не сможет выбежать со двора.

И еще я плакал, когда мамин врач позвонил, чтобы сообщить о случившемся на берегу: «Сожалею, но на спасение не было ни единого шанса. Иногда смерть наступает так внезапно, что врачи склонны видеть в этом благословение свыше».

Кристи при этом не присутствовала – ей пришлось допоздна задержаться в школе, чтобы встретиться с матерью одного ученика: у той возникли вопросы по его успеваемости, – но я плакал, будьте уверены. Пошел в нашу маленькую прачечную, достал из корзины с грязным бельем простыню и поплакал в нее. Не так чтобы долго, однако слезы были. Позже я мог рассказать об этом Кристи, но не видел смысла. По двум причинам. Она могла подумать, что я напрашиваюсь на жалость (у АА такой оборот не в ходу, но, может, им стоило бы взять его на вооружение). И к тому же я не считал залогом крепкой семейной жизни способность в надлежащий момент выжать из себя слезу.

Теперь, по здравом размышлении, я понимаю, что никогда не видел отца плачущим. В момент высшего эмоционального напряжения он тяжело вздыхал, порой с его губ слетали нервные смешки, но бить себя в грудь или гоготать – это не про Уильяма Эппинга. Я помню его строгим, молчаливым, и мать, по большей части, была ему под стать. Поэтому, возможно, отсутствие плаксивости заложено во мне генетически. Однако эмоциональный блок? Нечувствительность к собственным чувствам? Нет, это не про меня.

Не считая того момента, когда мне сообщили о смерти матери, взрослым я плакал, если не изменяет память, лишь однажды, читая историю отца уборщика. Сидел один в учительской средней школы Лисбона и проверял сочинения, написанные моими взрослыми учениками. Снизу доносился шум: удары баскетбольного мяча, свистки судьи, крики болельщиков, наблюдавших за звериным поединком: «Борзые Лисбона» схватились с «Тиграми Джея».

Кто может знать, когда жизнь зависнет на волоске или почему?

Тему я предложил такую: «День, который изменил мою жизнь». В большинстве своем сочинения получились искренние, но ужасные: сентиментальные байки о доброй тетушке, приютившей у себя беременную девушку-подростка, об армейском друге, проявившем настоящую храбрость, о случайной встрече со знаменитостью (вроде бы с Алексом Требеком, ведущим телевикторины «Риск», а может, с Карлом Молденом). Если среди вас есть учителя, которые зарабатывают дополнительные три-четыре тысячи долларов в год за преподавание в классе взрослых учеников, пожелавших получить Общий эквивалентный аттестат[1], они знают, какое тоскливое занятие – чтение таких сочинений. Необходимость выставить оценку не имеет к этому ни малейшего отношения, по крайней мере для меня: «неуд» я не ставлю никому, потому что никогда не встречал взрослого ученика, не проявлявшего должного старания. Если ты сдаешь сочинение, можешь не сомневаться, что Джейк Эппинг с кафедры английского языка и литературы ЛСШ[2] поставит тебе положительную отметку, а если текст разделен на абзацы, четверка с минусом точно гарантирована.

Труднее всего то, что учить их приходилось, просто исправляя ошибки – ручкой с красной пастой, и я практически всю ее исписывал. Тоска наваливалась потому, что очень малая часть пасты могла принести пользу: если ты дожил до двадцати пяти – тридцати лет, не зная, как правильно писать слова (полностью – не полнастью), или ставить прописные буквы (Белый дом – не белый-дом), или составлять предложения, содержащие и имя существительное, и глагол, – тебе этому уже никогда не научиться. И тем не менее мы продвигались вперед, смело обводя неправильно использованное либо лишнее слово, скажем, «очень» в предложении «Мой муж сразу решил, что все очень ясно», а также заменяя определенную форму глагола неопределенной, например, «испортится» на «испортиться» в вопросе «Ну что там могло испортится?».

В тот вечер я занимался этой бессмысленной, занудной работой, тогда как неподалеку баскетбольный матч между школьными командами приближался к завершению еще одной четверти… мир без конца, аминь. Происходило это вскоре после возвращения Кристи из реабилитационного центра, и, пожалуй, если я о чем-то и думал, то лишь об одном: надеялся, что, придя домой, увижу ее трезвой (так и случилось: за трезвость она держалась крепче, чем за мужа). Помнится, появилась легкая головная боль, и я массировал виски, чтобы неприятные ноющие ощущения не сменились размашистыми ударами парового молота. Я помню, как думал: Еще три штуки – и точка. Я пойду домой, налью большую чашку растворимого какао и окунусь в новый роман Джона Ирвинга, выкинув из головы эти искренние, но так плохо написанные сочинения.

Не заиграли скрипки, не зазвенели тревожные колокольчики, когда я взял сочинение уборщика, лежавшее первым в тоненькой стопке еще не прочитанных, и положил перед собой. Не возникло никакого ощущения, что в моей заурядной жизни грядут перемены. Но мы никогда не знаем, что нас ждет, ведь так? Жизнь может развернуться на пятачке.

Уборщик пользовался дешевой шариковой ручкой, паста во многих местах перепачкала все пять страниц, исписанных корявым, но разборчивым почерком, и он, похоже, очень сильно нажимал на ручку, потому что буквально выгравировал эти слова на бумаге. Закрыв глаза и пройдясь подушечками пальцев по обратной стороне вырванных листов, я мог бы прочесть текст, как по Брайлю. Каждая буква «у» снизу заканчивалась маленьким завитком, будто росчерком. Это я помню особенно ясно.

Помню я и начало его сочинения. Слово в слово.

Это был не день а вечер. Вечером который изменил мою жизнь, стал вечер когда мой отец убил мою мать и двух братьев и тежело ранил меня. От него досталось и моей сестре, и она ушла в кому. Через три года она умерла не очнувшись. Ее звали Эллен и я очень ее любил. Она любила собирать цвиты и ставеть их по вазам.

На середине первой страницы у меня защипало глаза, и я отложил мою верную красную ручку. А когда добрался до того места, где описывалось, как он залез под кровать, а кровь заливала ему глаза (она также стекала мне в горло, такая мерская на вкус), из моих собственных глаз покатились слезы – Кристи бы очень мной гордилась. Я дочитал до конца, не исправив ни единой ошибки, вытирая лицо, чтобы влага не размыла слова, которые, несомненно, дались ему с огромным трудом. Раньше я думал, что с головой у него хуже, чем у остальных, что он, возможно, только на полшага опережает тех, кого принято называть «поддающимися обучению умственно отсталыми». Что ж, клянусь Богом, на то была причина. Как и причина для хромоты. Просто чудо, что он вообще остался в живых. Но он выжил. Милый человек, который всегда улыбался и никогда не повышал голос на детей. Милый человек, который прошел через ад, а теперь стремился – смиренно и с надеждой, как большинство моих учеников, – получить аттестат средней школы. Хотя до конца жизни ему предстояло быть уборщиком, неприметным парнем в зеленой или коричневой униформе, шурующим шваброй и соскабливающим с пола жвачку шпателем, который он всегда носил в заднем кармане. Может, он и стал бы кем-то еще, но за один вечер жизнь его круто переменилась, и теперь он – лишь неприметный парень в «Кархарт»[3], прозванный школьниками Гарри-Жаба за походку.

Я плакал. Настоящими слезами, которые идут от самого сердца. До меня донесся победный марш школьного оркестра. То есть хозяева праздновали победу, и я мог только порадоваться за них. Позже, когда зал опустеет, Гарри и паре его коллег предстояло откатить трибуны и выгрести весь мусор, который набросали зрители.

Я поставил жирную красную пятерку в верхнем правом углу первого листа. Посмотрел на нее пару секунд, а потом добавил большой плюс. Потому что он написал хорошее сочинение и потому что его боль вызвала во мне, читателе, эмоциональную реакцию. А разве не это должно вызывать сочинение, за которое ставят пять с плюсом? Разве не эмоциональную реакцию?

Если же говорить обо мне, остается только сожалеть, что моя бывшая ошиблась. Увы, с эмоциональным блоком у нее вышла промашка. Потому что эти слезы стали началом всех последовавших событий – всех этих ужасов.

Часть I

Переломный момент

Глава 1

1

Гарри Даннинг окончил школу с отличием. Я пришел на небольшую церемонию вручения аттестатов взрослым ученикам, которая проводилась в спортивном зале ЛСШ, по его приглашению. А кого еще он мог пригласить? Я откликнулся с радостью.

После завершающей благодарственной молитвы, произнесенной отцом Бэнди, который редко пропускал мероприятия, проводимые в ЛСШ, я сквозь толпу родственников и друзей прошел к одиноко стоявшему Гарри, одетому в просторную черную мантию, с аттестатом в одной руке и взятой напрокат квадратной академической шапочкой в другой. Я забрал у него шапочку, чтобы пожать руку. Он улыбнулся, продемонстрировав оставшиеся зубы (некоторые были кривыми) и дыры между ними. Но улыбка все равно была солнечной и обаятельной.

– Спасибо, что пришли, мистер Эппинг. Огромное спасибо.

– Не за что. И называйте меня Джейк. Это маленькое послабление я делаю всем ученикам, которые по возрасту годятся мне в отцы.

На его лице отразилось недоумение, потом он рассмеялся:

– Действительно гожусь, да? Ну дела!

Я тоже рассмеялся. Вокруг многие смеялись. И разумеется, не обошлось без слез. Мне-то они давались с трудом, а большинству – легко.

– За всю жизнь ни разу не получал пятерку с плюсом! И не ожидал получить!

– Вы ее заслужили, Гарри. И что вы сделаете в первую очередь, имея на руках аттестат средней школы?

Улыбка на мгновение поблекла – так далеко он еще не заглядывал.

– Скорее всего пойду домой. Я снимаю домик на Годдард-стрит. – Он поднял аттестат, держа кончиками пальцев, словно боялся, что чернила могут размазаться: – Вставлю его в рамку и повешу на стену. Потом, наверное, налью стакан вина, сяду на диван и буду восхищаться им, пока не придет время ложиться спать.

– План неплохой, – кивнул я, – но как насчет того, чтобы сначала съесть бургер с жареной картошкой? Мы можем посидеть у Эла.

Я ожидал, что он поморщится, но, разумеется, так сделали бы разве что только мои коллеги. Нет, еще и большинство детей, которых мы учили. Забегаловку Эла они обходили как чумной барак, отдавая предпочтение «Дейри куин» напротив школы и кафе «Хай-хэт» на шоссе номер 196, рядом с тем местом, где когда-то находился старый автокинотеатр Лисбона.

– С удовольствием, мистер Эппинг. Спасибо!

– Джейк, помните?

– Джейк, точно.

И я отвез Гарри к Элу, куда другие учителя не заглядывали, и хотя в то лето Эл нанял официантку, он обслужил нас сам. Как обычно, с сигаретой (закон запрещает курение в барах, кафе и ресторанах, но Эла это никогда не останавливало), свисавшей из уголка рта, и прищуренным от дыма глазом. Увидев сложенную выпускную мантию и поняв, по какому случаю праздник, он настоял, что угостит нас за счет заведения (если на то пошло, все блюда у Эла стоили на удивление дешево, подпитывая определенные слухи о судьбе бродячих животных, заглянувших в окрестности забегаловки). Он также сфотографировал нас, чтобы потом повесить фотографию на так называемую Городскую стену славы. Среди других «знаменитостей», удостоенных этой чести, я видел ныне покойного Альберта Дантона, основателя ювелирного магазина «Ювелирные изделия Дантона», Эрла Хиггинса, бывшего директора ЛСШ, Джона Крафтса, владельца «Автомобильного салона Джона Крафтса», и, разумеется, отца Бэнди из церкви Святого Кирилла (рядом со святым отцом висела фотография папы Иоанна XXIII, который хоть и не был уроженцем Лисбона, но вызывал глубокое почтение у «доброго католика» Эла Темплтона). На фотографии, сделанной Элом в тот день, Гарри Даннинг улыбался во весь рот. Я стоял рядом с ним, и мы оба держали аттестат Гарри. Узел его галстука чуть съехал набок. Я помню это, потому что галстук навеял мысли о маленьких завитках, которыми заканчивались снизу буквы «у». Я все помню. Помню очень хорошо.

2

Двумя годами позже, в последний учебный день, я сидел в той самой учительской и читал итоговые сочинения, написанные участниками моего семинара по американской поэзии. Сами ученики уже ушли, у них начались летние каникулы, и в самом скором времени я собирался последовать их примеру. Но пока я наслаждался непривычной тишиной и покоем. Даже подумал, что перед уходом приберу полки буфета, где хранилась еда. Решил, что это обязательно нужно сделать.

В тот день, только раньше, вскоре после часов, отведенных на самостоятельные занятия (в последний учебный день они бывают особенно шумными что в классах для выполнения домашних заданий, что в коридорах), ко мне, прихрамывая, подошел Гарри и протянул руку:

– Просто хочу поблагодарить вас за все.

Я улыбнулся:

– Вы уже поблагодарили, как мне помнится.

– Да, но это мой последний день. Ухожу на пенсию. Поэтому захотел подойти и поблагодарить еще раз.

Когда я пожимал его руку, проходивший мимо подросток (девятиклассник, никак не старше, если судить по свежей россыпи прыщей и комичной щетине, которую он пытался превратить в козлиную бородку) пробормотал:

– Гарри-Жаба прыгает по а-ве-ню!

Я попытался ухватить его за плечо, чтобы он извинился, но Гарри меня остановил. По его улыбке чувствовалось, что он нисколько не обиделся.

– Не берите в голову. Я к этому привык. Это же дети.

– Совершенно верно, – кивнул я. – И наша работа – учить их.

– Я знаю, и у вас получается. Но это не моя работа – служить для кого-то… как это называется… наглядным пособием. Особенно сегодня. Надеюсь, все у вас будет хорошо, мистер Эппинг.

По возрасту он, возможно, годился мне в отцы, но называть меня Джейком у него не получалось.

– И у вас тоже, Гарри.

– Я никогда не забуду ту пятерку с плюсом. Сочинение тоже поместил в рамочку. Висит у меня на стене рядом с аттестатом.

– И это правильно.

Я не кривил душой. Я верил, что это правильно. Воспринимал его сочинение как произведение примитивного искусства, ничуть не уступающее по мощи воздействия и искренности картинам Бабушки Мозес[4]. Оно на порядок превосходило сочинения, которые я сейчас читал. Пусть в них практически не было орфографических ошибок и слова мои ученики выбирали правильно (хотя эти нацелившиеся на колледж перестраховщики тяготели – что раздражало – к частому использованию страдательного залога), но сочинения получались пресными. Скучными. Участники моего семинара учились в предвыпускном классе (выпускников Мак Стидман, заведующий кафедрой, забирал себе), да только писали они, как старички и старушки: «О-о-о, Милдред, душечка, там лед, смотри не поскользнись». Гарри Даннинг, несмотря на ошибки и натужный почерк, писал, как полубог. Хотя бы один раз.

И пока я размышлял о разнице между энергичной и инертной манерами письма, прокашлялся настенный аппарат внутренней связи.

– Мистер Эппинг все еще в учительской западного крыла? Джейк, ты на месте?

Я поднялся, нажал кнопку.

– На месте, Глория. Грехи не отпускают. Чем я могу тебе помочь?

– Тебе звонят. Какой-то Эл Темплтон. Если хочешь, могу перевести звонок на учительскую. Или скажу ему, что ты уже ушел.

Эл Темплтон – владелец и шеф-повар «Закусочной Эла», которую наотрез отказывались посещать все учителя ЛСШ, за исключением вашего покорного слуги. Даже мой глубокоуважаемый заведующий кафедрой – пытавшийся говорить как маститый преподаватель Кембриджа и приближавшийся к пенсионному возрасту – называл фирменное блюдо закусочной «Знаменитый котобургер Эла», хотя в меню значился «Знаменитый толстобургер Эла».

Возможно, это не кошатина, как утверждают многие, наверняка не кошатина, но это и не говядина, не может это быть говядиной за доллар девятнадцать.

– Джейк? Ты что, уснул?

– Нет, сна ни в одном глазу. – Меня разбирало любопытство: с чего это Эл сподобился позвонить мне в школу? Если на то пошло, раньше он вообще никогда не звонил. Наши отношения не выходили за рамки повар – клиент. Я высоко ценил его кулинарное мастерство, а он – мои регулярные визиты. – Конечно, соедини меня.

– А что ты там до сих пор делаешь?

– Занимаюсь самобичеванием.

– О-о-о, – простонала Глория, и я легко представил, как затрепетали ее длинные ресницы. – Как мне нравится, когда ты так говоришь. Жди звоночка.

Она отключила связь. Тут же зазвонил телефон, и я снял трубку.

– Джейк? Это ты, дружище?

Поначалу я подумал, что Глория напутала с именем. Этот голос никак не мог принадлежать Элу. При самой жуткой простуде он не мог так хрипеть.

– Кто это?

– Эл Темплтон, разве она не сказала? Боже, от вашей музыкальной заставки просто тошнит. Что случилось с Конни Фрэнсис? – Он начал так громко и надсадно кашлять, что я отодвинул трубку от уха.

– Ты, похоже, подхватил грипп.

Он рассмеялся, продолжая кашлять. Сочетание получилось не из лучших.

– Что-то я подхватил, это точно.

– Быстро же тебя скрутило.

Я заглядывал к нему вчера, на ранний ужин: толстобургер, картофель фри, клубничный молочный коктейль. Считаю, что человеку, который живет один, необходимо сбалансированное питание.

– Можно сказать и так. А можно сказать, что какое-то время мой организм боролся. Оба варианта правильные.

Я не знал, что на это ответить. За последние шесть или семь лет мы часто болтали с Элом, когда я приходил в его закусочную, и иной раз он вел себя довольно странно – скажем, называл «Патриотов Новой Англии»[5] «Бостонскими патриотами», а о Тэде Уильямсе[6] говорил так, будто знал его, как брата, – но столь необычного разговора я припомнить не мог.

– Джейк, мне надо с тобой увидеться. Это важно.

– Могу я спросить…

– Я уверен, ты задашь не один вопрос, и я отвечу на все, но не по телефону.

Я не знал, сколько ответов услышу до того, как его голос окончательно сядет, но пообещал, что буду примерно через час.

– Спасибо. Если сможешь, постарайся побыстрее. Не зря же говорят, что время – деньги.

И он положил трубку. Взял и положил, не попрощавшись.

Я прочитал еще два сочинения. В стопке осталось только четыре, но раскрывать их я не стал. Пропал настрой. В итоге смахнул оставшиеся работы в портфель и отбыл. Мелькнула мысль, а не подняться ли наверх, в секретариат, чтобы пожелать удачного лета Глории, но я решил, что необходимости в этом нет. Я знал, что всю следующую неделю она проведет в школе – будет заниматься подготовкой отчета за учебный год, – а я собирался прийти сюда в понедельник, чтобы очистить полки буфета: дал себе слово. Иначе преподаватели, решившие летом использовать западную учительскую, обнаружат, что она кишит тараканами.

Если бы я мог предположить, что меня ждет, обязательно поднялся бы наверх повидаться с Глорией. Возможно, одарил бы ее поцелуем, который словно висел между нами в воздухе последнюю пару месяцев. Но разумеется, я не знал, что меня ждет. Жизнь может развернуться на пятачке.

3

«Закусочная Эла» – серебристый трейлер, отделенный от Главной улицы железнодорожными путями, – стояла в тени старой фабрики Ворамбо. Такие забегаловки обычно смотрятся неприглядно, но Эл разбил цветочные клумбы перед бетонными блоками, на которых размещался трейлер. Здесь даже нашлось место лужайке, и Эл аккуратно выкашивал ее старомодной механической косилкой, за которой ухаживал ничуть не меньше, чем за клумбами и газоном. Ни единого пятнышка ржавчины не темнело на сверкающих, заточенных ножах. Если судить по внешнему виду, косилку могли купить неделей раньше в магазине «Уэстерн авто»… если бы такой магазин еще существовал, а не пал жертвой гипермаркетов.

Я прошел по мощеной дорожке, поднялся по ступеням и остановился, нахмурившись. Вывеска с надписью «ДОБРО ПОЖАЛОВАТЬ В «ЗАКУСОЧНУЮ ЭЛА» – ДОМ ТОЛСТОБУРГЕРА!» исчезла. Ее место занял квадратный кусок картона, гласивший: «ЗАКРЫТО И БОЛЬШЕ НЕ ОТКРОЕТСЯ В СВЯЗИ С БОЛЕЗНЬЮ ВЛАДЕЛЬЦА. СПАСИБО, ЧТО ПРИХОДИЛИ ДОЛГИЕ ГОДЫ, И ДА БЛАГОСЛОВИТ ВАС ГОСПОДЬ».

Я еще не канул в туман нереальности, которому предстояло вскоре поглотить меня, но первые его щупальца уже начали приближаться, и я их почувствовал. Летняя простуда не могла вызвать те хрипы в голосе Эла, тот надсадный кашель. И грипп тоже. Судя по объявлению, речь шла о чем-то более серьезном. Но какая тяжелая болезнь способна так развиться за двадцать четыре часа? Даже меньше? Часы показывали половину третьего. Вчера вечером я ушел от Эла без четверти шесть, и он прекрасно себя чувствовал. Пребывал в очень приподнятом настроении, чуть ли не в экзальтации. Помнится, я спросил его, не многовато ли он пьет кофе собственного приготовления, и он ответил, что нет, просто думает о том, чтобы взять отпуск. Разве люди, которые заболевают, причем так тяжело, чтобы закрыть заведение, где в одиночку хозяйничали больше двадцати лет, говорят о намерении уйти в отпуск? Кто-то, возможно, и говорит, но не так чтобы многие.

Дверь открылась, как только я потянулся к ручке, и за порогом стоял Эл, глядя на меня без тени улыбки. Я смотрел на него, чувствуя, как сгущается туман нереальности. День выдался теплым, но мне стало холодно. В этот момент еще можно было повернуться и уйти, выбраться на июньское солнце, и в глубине я хотел это сделать, однако застыл от изумления и испуга. А также от ужаса, готов признать. Тяжелая болезнь всегда пугает нас, правда? А в том, что Эл тяжело болен, сомнений быть не могло. Я это понял с первого взгляда. Я бы даже сказал, что он болен смертельно.

Поражало не то, что обычно румяные щеки Эла ввалились и побледнели. И не то, что какие-то выделения сочились из уголков его голубых глаз, теперь выцветших и сощуренных, как при близорукости. И не то, что практически черные волосы стали совсем седыми, – в конце концов, он мог пользоваться красящим бальзамом, а тут вдруг смыл его, и волосы приняли естественный цвет.

Дело было в другом: за двадцать два часа, прошедших с нашей последней встречи, Эл Темплтон похудел как минимум на тридцать фунтов. Может, на сорок, то есть потерял четверть своего прежнего веса. Никто не может похудеть за день на тридцать или сорок фунтов, никто. Но я видел перед собой такого человека. Вот тут-то туман нереальности и накрыл меня с головой.

Эл улыбнулся, и стало понятно, что, кроме веса, он потерял еще и зубы. Десны выглядели бледными и нездоровыми.

– Как тебе нравится такой Эл, Джейк? – спросил он и закашлялся, хриплые, лающие звуки поднимались откуда-то из глубины груди.

Я открыл рот. Но с губ не сорвалось ни звука. Вновь появилось трусливое мерзкое желание бежать отсюда, однако я не смог бы этого сделать, даже если бы захотел. Ноги просто приросли к полу.

Эл обуздал кашель и вытащил из заднего кармана носовой платок. Вытер рот, потом ладонь. Прежде чем Эл убрал платок, я заметил на нем кровь.

– Заходи. Мне надо многое рассказать, и я думаю, что выслушать меня можешь только ты. Выслушаешь?

– Эл… – Мой голос звучал так тихо, что я сам едва слышал его. – Что с тобой случилось?

– Ты выслушаешь меня?

– Разумеется.

– У тебя будут вопросы, я постараюсь ответить на те, что смогу, но ты уж сведи их к минимуму. Не знаю, долго ли смогу говорить. Черт, да и сил осталось не много. Заходи.

Я вошел. Увидел, что в помещении сумрачно, и прохладно, и пусто. Чистая, без единой крошки, стойка. Поблескивающие хромом высокие стулья. Сверкающий никелем кофейник. И табличка «ЕСЛИ ТЕБЕ НЕ НРАВИТСЯ НАШ ГОРОД, ПОИЩИ РАСПИСАНИЕ» на положенном месте у кассового аппарата. Недоставало только посетителей.

И разумеется, повара-владельца. Место Эла Темплтона занял пожилой, болезненный призрак. Когда он повернул защелку, запирая дверь, по залу разнесся слишком громкий звук.

4

– Рак легких, – буднично объяснил Эл, когда мы устроились в одной из кабинок в глубине зала. Похлопал по нагрудному карману рубашки, и я заметил, что он пуст. Всегда лежавшая в нем пачка «Кэмела» без фильтра исчезла. – Неудивительно. Я начал курить в одиннадцать и бросил, лишь когда мне поставили диагноз. Более пятидесяти чертовых лет. Три пачки в день, пока в две тысячи седьмом не подскочила цена. Тогда пришлось пойти на жертвы и ограничиться двумя пачками. – Он сипло рассмеялся.

Я хотел было сказать ему, что у него не все в порядке с математикой, поскольку знал его настоящий возраст. Как-то в конце зимы я пришел в забегаловку, а он стоит за грилем в детской шляпе с надписью «С днем рождения». Я спросил, по какому поводу, и он ответил: «Сегодня мне пятьдесят семь, дружище. Так что можешь звать меня Хайнцем»[7]. Но Эл попросил задавать только те вопросы, которые я сочту абсолютно необходимыми, и корректировка возраста в них не входила.

– На твоем месте – а я бы с радостью на нем оказался, хотя совершенно не хочу, чтобы ты попал на мое, при нынешнем раскладе, – я бы подумал: «Здесь какая-то лажа. За одну ночь рак не может так далеко зайти». Правильно?

Я кивнул. Конечно же, правильно.

– Ответ прост. Он так далеко зашел не за одну ночь. Я начал выхаркивать мозги примерно семь месяцев назад, где-то в мае.

Что ж, он меня удивил. Если он и выхаркивал мозги, то не в моем присутствии. И опять у него произошла математическая накладка.

– Эл, ты что? Сейчас июнь. Если отсчитать семь месяцев назад, будет декабрь.

Он помахал рукой – пальцы стали совсем тонкими, перстень морпехов свободно болтался, хотя раньше сидел плотно, – как бы говоря: «Давай не будем терять на это время».

– Сначала я думал, что сильно простудился. Но температура не поднялась, а кашель, вместо того чтобы пройти, только усиливался. И я начал худеть. Что ж, я не идиот, дружище, и всегда знал, что могу вытащить карту с большой буквой «Р»… хотя мои отец и мать дымили как чертовы заводские трубы и прожили больше восьмидесяти лет. Вечно мы находим оправдания своим вредным привычкам, верно?

Он опять закашлялся, достал носовой платок. Когда приступ закончился, Эл продолжил:

– У меня нет времени переводить разговор на другую тему, но я это делал всю жизнь, и трудно теперь отказаться. Если хочешь знать, труднее, чем от сигарет. В следующий раз, когда меня потянет в сторону, проведи пальцем по горлу, хорошо?

– Хорошо, – согласился я. Мелькнула мысль, что мне все это снится. Если так, сон получился очень уж реальный, даже с тенями от лопастей медленно вращающегося потолочного вентилятора на салфетках с надписью «САМАЯ БОЛЬШАЯ НАША ЦЕННОСТЬ – ЭТО ВЫ».

– Короче говоря, я отправился к врачу, сделал рентген, и они выявились, большие, как чертовы яйца, две опухоли. Прогрессирующий некроз. Неоперабельные.

Рентген, подумал я. Неужели до сих пор используют рентген, чтобы диагностировать рак?

– Какое-то время я там поболтался, но в итоге мне пришлось вернуться.

– Откуда? Из Льюистона? Из Центральной больницы штата Мэн?

– Из моего отпуска. – Он пристально смотрел на меня. – Только это был не отпуск.

– Эл, я ничего не понимаю. Вчера ты был здесь и прекрасно себя чувствовал.

– Внимательно присмотрись к моему лицу. Начни с волос и продвигайся вниз. Постарайся не замечать воздействия рака – он сильно меняет внешность человека, в этом сомнений нет, – а потом скажи, тот ли я человек, которого ты видел вчера.

– Что ж, ты, очевидно, смыл краску…

– Никогда ею не пользовался. Не буду обращать твое внимание на зубы, которые потерял, пока находился… далеко. Я знаю, ты это заметил. Думаешь, это воздействие рентгеновского аппарата? Или стронция-девяносто в молоке? Я никогда не пью молоко, разве что добавляю капельку в последнюю за день чашку кофе.

– Какого стронция?

– Не важно. Попробуй посмотреть на меня, как женщины смотрят на других женщин, когда хотят определить возраст.

Я попытался последовать его совету, и хотя любой суд откажется принять мои наблюдения в качестве доказательств, меня они убедили. От уголков глаз расходились паутинки морщинок, хватало их, маленьких и тонких, и на веках, как у всех тех, кому больше не приходится доставать дисконтную пенсионную карточку, подходя к кассе многозального кинотеатра. Отсутствовавшие вчера бороздки синусоидами пересекали лоб. Еще две морщины, гораздо более глубокие, отходили от уголков рта. Подбородок заострился, кожа на шее обвисла. Острый подбородок и обвисшую кожу я мог отнести к катастрофической потере веса, но эти морщины… и если он не лгал о волосах…

Эл еле заметно улыбался. Мрачновато, но не без юмора. И от его улыбки мне стало совсем тошно.

– Помнишь мой день рождения в начале марта? «Не волнуйся, Эл, – сказал ты, – если эта дурацкая шляпа загорится, когда ты наклонишься над грилем, я схвачу огнетушитель и потушу тебя». Помнишь?

Я помнил.

– Ты сказал, что теперь я могу называть тебя Хайнцем.

– Да. А теперь мне шестьдесят два. Я знаю, из-за рака выгляжу старше, но это… и это… – Он коснулся сначала лба, потом уголка глаза. – Это естественные возрастные татуировки. Знаки доблести, если хочешь.

– Эл… я бы выпил стакан воды.

– Конечно. Шок, правда? – Он сочувственно посмотрел на меня. – Ты думаешь: «Или я сошел с ума, или он, или мы оба». Знаю. Я это уже проходил.

Не без усилия он вылез из кабинки, ухватившись правой рукой за левую подмышку, словно опасался, что развалится. Потом повел меня за стойку. И пока мы шли, я отметил еще один нюанс этой нереальной встречи: за исключением тех случаев, когда мы делили скамью в церкви Святого Кирилла (такое бывало редко; хотя меня и воспитывали в вере, католик я плохой) или встречались на улице, я никогда не видел Эла без его поварского фартука.

Он снял с полки сверкающий стакан и налил мне воды из поблескивающего хромом крана. Я поблагодарил его и повернулся, чтобы вернуться в кабинку, но он похлопал меня по плечу. Лучше бы он этого не делал. Казалось, меня коснулась рука кольриджского древнего морехода[8], остановившего одного из троих.

– Я хочу, чтобы ты увидел кое-что, прежде чем мы снова сядем. Так будет быстрее. Только «увидел» – слово неправильное. Точнее – испытал. Пей, дружище.

Я выпил полстакана холодной вкусной воды, но при этом не отрывал глаз от Эла. Я словно трусливо ожидал, что на меня сейчас набросятся, как на первую, ничего не подозревающую жертву фильма о маньяках, в названии которого обязательно присутствует цифра. Но Эл просто стоял, опираясь рукой о стойку. Морщинистая кожа, большие костяшки. Определенно не рука человека, которому только под шестьдесят, пусть и больного раком. А еще…

– Это результат воздействия радиации? – спросил я.

– Что?

– Ты загорелый. Я не говорю про темные пятна на тыльной стороне ладоней. Такое бывает или от радиации, или от слишком долгого пребывания на солнце.

– Раз курс лучевой терапии я не проходил, остается солнце. За последние четыре года я провел много времени на солнце.

Насколько я знал, большую часть последних четырех лет Эл жарил бургеры и взбивал молочные коктейли под флуоресцентными лампами, но говорить об этом не стал. Допил воду. Когда ставил стакан на пластиковую стойку, заметил, что моя рука немного трясется.

– Ладно, так что я должен увидеть? Или испытать?

– Иди сюда.

Он повел меня по узкому проходу мимо двустороннего гриля, фритюрниц, раковины, холодильника «Фросткинг», гудящей морозильной камеры высотой по пояс. Остановился перед выключенной посудомоечной машиной и указал на дверь в конце кухни. Низкую дверь. Элу, ростом пять футов и семь дюймов или около того, приходилось наклоняться, чтобы войти в нее. Меня, с моими шестью футами и четырьмя дюймами, некоторые ученики называли Эппинг-Вертолет.

– Вот, – кивнул он. – Войди в эту дверь.

– Разве у тебя там не кладовка? – Вопрос был риторический. За долгие годы я не раз и не два видел, как он выносил оттуда банки, сетки с картофелем, пакеты с бакалеей, и точно знал, что находится за дверью.

Эл меня вроде бы и не услышал.

– Ты знал, что сначала я открыл это заведение в Оберне?

– Нет.

Он кивнул, и этого хватило, чтобы вызвать очередной приступ кашля. Эл подавил его платком, на котором расплывались все новые красные пятна. Когда кашель наконец стих, он бросил платок в мусорное ведро и взял несколько салфеток из коробки на стойке.

– Этот трейлер – «Алюминейр», сделан в тридцатых годах в стиле ар деко. Я такой хотел с тех пор, как отец ребенком взял меня в «Жуй-и-болтай» в Блумингтоне. Купил его полностью оборудованным и открыл закусочную на Сосновой улице. Пробыв там год, понял, что разорюсь, если останусь. По соседству хватало ресторанов и кафе быстрого обслуживания, хороших и не очень, но со своей клиентурой. Я же напоминал юношу, который только что окончил юридическую школу и пытается практиковать в городе, где уже работает с десяток уважаемых адвокатских контор. Опять же, тогда «Знаменитый толстобургер Эла» стоил два с половиной бакса. И в девяностом году за меньшую цену я его продавать не мог.

– Тогда какого черта сейчас ты продаешь его в два раза дешевле? Если только это все-таки не кошатина.

Он фыркнул, и звук этот эхом отдался глубоко у него в груди.

– Дружище, я продаю стопроцентно чистую американскую говядину, лучшую в мире. Известно ли мне, что говорят люди? Естественно. Я не обращаю на это внимания. Что тут поделаешь? Затыкать им рты? С тем же успехом можно пытаться не давать ветру дуть.

Я провел пальцем по шее. Эл улыбнулся:

– Да, ухожу в сторону, но по крайней мере цена говядины – часть истории. Я мог бы и дальше биться головой о стенку на Сосновой улице, однако Ивонн Темплтон дураков не воспитывала. «Лучше убегите и подеритесь в другой день», – говорила она нам в детстве. Я собрал оставшиеся деньги, выпросил в банке еще пять тысяч ссуды – не спрашивай как – и перебрался в Фоллс. Сверхприбыли по-прежнему нет – экономика не в том состоянии, а еще эти глупые разговоры о котобургерах, или песобургерах, или скунсобургерах, у людей фантазия богатая, – да только теперь я не зависел от экономики, как все остальные. И причина тому – за этой дверью в кладовку. В Оберне за ней ничего особенного не было. Я готов поклясться в этом на стопке Библий высотой десять футов. Все проявилось только здесь.

– О чем ты?

Он пристально посмотрел на меня водянистыми, за ночь постаревшими глазами:

– Сейчас говорить больше не о чем. Тебе надо все увидеть самому. Вперед, открой дверь.

На моем лице наверняка читалось сомнение. Эл подбодрил меня:

– Считай, это последняя просьба умирающего. Давай, дружище. Если только ты мне друг. Открой дверь.

5

Я бы солгал, сказав, что бег сердца не ускорился, когда я повернул ручку и потянул дверь на себя. Я понятия не имел, с чем могу столкнуться (хотя, помнится, в голове мелькнул образ дохлых кошек, освежеванных и готовых к превращению в фарш в электрической мясорубке), но когда Эл протянул руку и включил свет, я увидел, что за дверью…

Всего лишь кладовка.

Маленькая, такая же ухоженная и опрятная, как и вся закусочная. На полках вдоль стен – большие, ресторанной расфасовки, банки консервов. В дальнем конце, где крыша плавно шла вниз, нашлось место порошкам и прочим чистящим средствам. Щетка и швабра лежали на полу, потому что потолок и пол разделяли только три фута. Пол застилал тот же серый линолеум, но пахло не жареным мясом, как в зале, а кофе, овощами и специями. Ощущался и еще какой-то запах, слабый и не очень приятный.

– Ладно, – кивнул я, – это кладовка. Много всего, все аккуратно сложено. По управлению припасами, если такой предмет существует, ставлю тебе пятерку.

– Чем тут пахнет?

– В основном специями. Кофе. Может, еще освежителем воздуха. Не знаю.

– Да, я использую «Глейд». Из-за того запаха. Ты хочешь сказать, что больше ничего не чувствуешь?

– Что-то есть. Похоже на серу. Наводит на мысли о горелых спичках. – Я также подумал и об отравляющем газе, что мы всей семьей испускали после тушеных бобов, которые мама обычно готовила на субботний ужин, но не упомянул об этом. А может, лекарства от рака вызывают пердеж?

– Это сера. Есть и другие запахи, тоже не «Шанель номер пять». Фабричная вонь, дружище.

Безумие продолжалось, но я смог ответить лишь (да и то абсурдно-вежливым тоном, принятым на коктейльной вечеринке):

– Правда?

Эл опять улыбнулся, продемонстрировав десны, из которых всего днем раньше выступали ровные зубы.

– Ты вежливо намекаешь, что фабрика Ворамбо закрылась, когда меня еще на свете не было? Если на то пошло, в конце восьмидесятых она сгорела почти дотла, а то, что осталось, – он ткнул пальцем себе за плечо, – всего лишь склад-магазин готовой продукции. Одна из главных туристических достопримечательностей, наряду с «Кеннебек фрут компани», где продают «Мокси». И еще ты думаешь, что сейчас самое время достать мобильник и вызвать парней в белых халатах. Так ведь, дружище?

– Я никому не собираюсь звонить, потому что ты не псих. – Правда, я сам не верил в то, что говорил. – Но это всего лишь кладовка, а фабрика Ворамбо за последнюю четверть века не выткала ни рулона ткани.

– Ты никому не позвонишь, это точно, поскольку я хочу, чтобы ты отдал мне мобильник, бумажник и все деньги, что у тебя в карманах, включая монеты. Это не ограбление. Я тебе все верну. Ты отдашь мне эти вещи?

– Сколько у меня уйдет на это времени, Эл? Мне нужно прочитать несколько сочинений, чтобы выставить итоговые оценки за этот учебный год.

– Оставайся там сколько хочешь, – ответил Эл, – потому что это займет две минуты. Это всегда занимает две минуты. Останься на час и как следует осмотрись, если возникнет желание, но я бы этого делать не стал, во всяком случае, в первый раз, потому что потрясение будет слишком велико. Ты сам увидишь. Доверишься мне? – Что-то в моем лице заставило его напрячься. – Пожалуйста. Пожалуйста, Джейк. Желание умирающего.

Я уже точно знал, что Эл безумен, но знал и другое: он не ошибается по части своего состояния. За время нашего недолгого разговора его глаза, казалось, еще глубже погрузились в глазницы. И он совершенно выдохся. Двух десятков шагов от кабинки в одном конце закусочной до кладовки в другом хватило для того, чтобы он покачивался, едва держась на ногах. «И еще окровавленный носовой платок, – напомнил я себе. – Не забывай про окровавленный носовой платок».

И… я понял, что проще пойти ему навстречу. Вы со мной не согласны?

«Не противься, и пусть будет по-Божьему» – так им нравится говорить на собраниях, которые посещает моя бывшая, но я решил, что тут все иначе: не противься, и пусть все будет, как хочет Эл. Во всяком случае, до какого-то предела. И почему нет? – сказал я себе. Когда садишься в самолет приходится пройти через большую хренотень. А Эл даже не попросил меня снять обувь и поставить на транспортер.

Я вытащил мобильник из чехла на ремне, положил на картонную коробку с банками консервированного тунца. Добавил бумажник, тонкую пачку купюр, доллар пятьдесят или чуть больше мелочью и кольцо с ключами.

– Ключи оставь, они значения не имеют.

Для меня имели, но я промолчал.