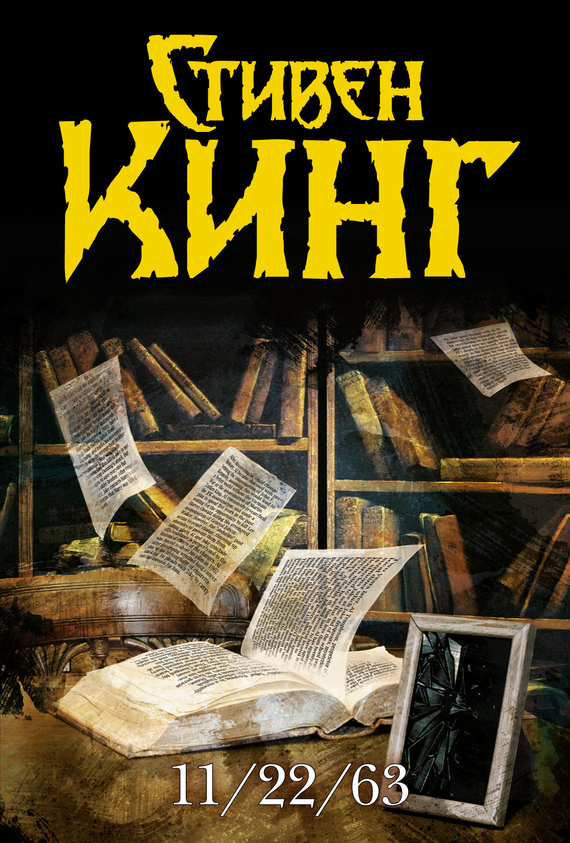

11/22/63 Êèíã Ñòèâåí

“I will if you tell me you’re awake.”

“I’m awake.” She looked at me with churlish resentment and—maybe—the tiniest glint of humor. “You certainly know how to make an entrance, George.”

I turned to the medicine cabinet.

“There aren’t any more,” she said. “What isn’t in me is in the commode.”

Having been married to Christy for four years, I looked anyway. Then I flushed the toilet. With that business taken care of, I slipped past her to the bathroom door. “I’ll give you three minutes,” I said.

9

The return address on the manila envelope was John Clayton, 79 East Oglethorpe Avenue, Savannah, Georgia. You certainly couldn’t accuse the bastard of flying under false colors, or going the anonymous route. The postmark was August twenty-eighth, so it had probably been waiting here for her when she got back from Reno. She’d had nearly two months to brood over the contents. Had she sounded sad and depressed when I’d talked to her on the night of September sixth? Well, no wonder, given the photographs her ex had so thoughtfully sent her.

We’re all in danger, she’d said the last time I spoke to her on the phone. Johnny’s right about that.

The pictures were of Japanese men, women, and children. Victims of the atomic bomb-blasts at Hiroshima, Nagasaki, or both. Some were blind. Many were bald. Most were suffering from radiation burns. A few, like the faceless woman, had been charbroiled. One picture showed a quartet of black statues in cringing postures. Four people had been standing in front of a wall when the bomb went off. The people had been vaporized, and most of the wall had been vaporized, too. The only parts that remained were the parts that had been shielded by those standing in front of it. The shapes were black because they were coated in charred flesh.

On the back of each picture, he had written the same message in his clear, neat hand: Coming soon to America. Statistical analysis does not lie.

“Nice, aren’t they?”

Her voice was flat and lifeless. She was standing in the doorway, bundled into the towel. Her hair fell to her bare shoulders in damp ringlets.

“How much did you have to drink, Sadie?”

“Only a couple of shots when the pills wouldn’t work. I think I tried to tell you that when you were shaking and slapping me.”

“If you expect me to apologize, you’ll wait a long time. Barbiturates and booze are a bad combination.”

“It doesn’t matter,” she said. “I’ve been slapped before.”

That made me think of Marina, and I winced. It wasn’t the same, but slapping is slapping. And I had been angry as well as scared.

She went to the chair in the corner, sat down, and pulled the towel tighter around her. She looked like a sulky child. “My friend Roger Beaton called. Did I tell you that?”

“Yes.”

“My good friend Roger.” Her eyes dared me to make something of it. I didn’t. Ultimately, it was her life. I just wanted to make sure she had a life.

“All right, your good friend Roger.”

“He told me to be sure and watch the Irish asshole’s speech tonight. That’s what he called him. Then he asked me how far Jodie was from Dallas. When I told him he said, ‘That should be far enough, depending on which way the wind’s blowing.’ He’s getting out of Washington himself, lots of people are, but I don’t think it will do them any good. You can’t outrun a nuclear war.” She began to cry then, harsh and wrenching sobs that shook her whole body. “Those idiots are going to destroy a beautiful world! They’re going to kill children! I hate them! I hate them all! Kennedy, Khrushchev, Castro, I hope they all rot in hell!”

She covered her face with her hands. I knelt like some old-fashioned gentleman preparing to propose and embraced her. She put her arms around my neck and clung to me in what was almost a drowner’s grip. Her body was still cold from the shower, but the cheek she laid against my arm was feverish.

In that moment I hated them all, too, John Clayton most of all for planting this seed in a young woman who was insecure and psychologically vulnerable. He had planted it, watered it, weeded it, and watched it grow.

And was Sadie the only one in terror tonight, the only one who had turned to the pills and the booze? How hard and fast were they drinking in the Ivy Room right now? I’d made the stupid assumption that people were going to approach the Cuban Missile Crisis much like any other temporary international dust-up, because by the time I went to college, it was just another intersection of names and dates to memorize for the next prelim. That’s how things look from the future. To people in the valley (the dark valley) of the present, they look different.

“The pictures were here when I got back from Reno.” She looked at me with her bloodshot, haunted eyes. “I wanted to throw them away, but I couldn’t. I kept looking at them.”

“It’s what the bastard wanted. That’s why he sent them.”

She didn’t seem to hear. “Statistical analysis is his hobby. He says that someday, when the computers are good enough, it will be the most important science, because statistical analysis is never wrong.”

“Not true.” In my mind’s eye I saw George de Mohrenschildt, the charmer who was Lee’s only friend. “There’s always a window of uncertainty.”

“I guess the day of Johnny’s super-computers will never come,” she said. “The people left—if there are any—will be living in caves. And the sky… no more blue. Nuclear darkness, that’s what Johnny calls it.”

“He’s full of shit, Sadie. Your pal Roger, too.”

She shook her head. Her bloodshot eyes regarded me sadly. “Johnny knew the Russians were going to launch a space satellite. We were just out of college then. He told me in the summer, and sure enough, they put Sputnik up in October. ‘Next they’ll send a dog or a monkey,’ Johnny said. ‘After that they’ll send a man. Then they’ll send two men and a bomb.’”

“And did they do that? Did they, Sadie?”

“They sent the dog, and they sent the man. The dog’s name was Laika, remember? It died up there. Poor doggy. They won’t have to send up the two men and the bomb, will they? They’ll use their missiles. And we’ll use ours. All over a shitpot island where they make cigars.”

“Do you know what the magicians say?”

“The—? What are you talking about?”

“They say you can fool a scientist, but you can never fool another magician. Your ex may teach science, but he’s sure no magician. The Russians, on the other hand, are.”

“You’re not making sense. Johnny says the Russians have to fight, and soon, because now they have missile superiority, but they won’t for long. That’s why they won’t back down in Cuba. It’s a pretext.”

“Johnny’s seen too much newsreel footage of missiles being trundled through Red Square on Mayday. What he doesn’t know—and what Senator Kuchel doesn’t know, either, probably—is that over half of those missiles don’t have engines in them.”

“You don’t… you can’t…”

“He doesn’t know how many of their ICBMs blow up on their launch pads in Siberia because their rocketry guys are incompetent. He doesn’t know that over half the missiles our U-2 planes have photographed are actually painted trees with cardboard fins. It’s sleight of hand, Sadie. It fools scientists like Johnny and politicians like Senator Kuchel, but it would never fool another magician.”

“That’s… it’s not…” She fell silent for a moment, biting at her lips. Then she said, “How could you know stuff like that?”

“I can’t tell you.”

“Then I can’t believe you. Johnny said Kennedy was going to be the nominee of the Democratic party, even though everybody else thought it was going to be Humphrey on account of Kennedy being a Catholic. He analyzed the states with primaries, ran the numbers, and he was right. He said Johnson would be Kennedy’s running mate because Johnson was the only Southerner who would be acceptable north of the Mason-Dixon line. He was right about that, too. Kennedy got in, and now he’s going to kill us all. Statistical analysis doesn’t lie.”

I took a deep breath. “Sadie, I want you to listen to me. Very carefully. Are you awake enough to do that?”

For a moment there was nothing. Then I felt her nod against my upper arm.

“It’s now early Tuesday morning. This standoff is going to go on for another three days. Or maybe it’s four, I can’t remember.”

“What do you mean, you can’t remember?”

I mean there’s nothing about this in Al’s notes, and my only college class in American History was almost twenty years ago. It’s amazing I can remember as much as I do.

“We’re going to blockade Cuba, but the only Russian ship we’ll stop won’t have anything in it but food and trade goods. The Russians are going to bluster, but by Thursday or Friday they’re going to be scared to death and looking for a way out. One of the big Russian diplomats will initiate a backchannel meeting with some TV guy.” And seemingly from nowhere, the way crossword puzzle answers sometimes come to me, I remembered the name. Or almost remembered it. “His name is John Scolari, or something like that—”

“Scali? Are you talking about John Scali, on the ABC News?”

“Yeah, that’s him. This is going to happen Friday or Saturday, while the rest of the world—including your ex and your pal from Yale—is just waiting for the word to stick their heads between their legs and kiss their asses goodbye.”

She heartened me by giggling.

“This Russian will more or less say…” Here I did a pretty good Russian accent. I had learned it listening to Lee’s wife. Also from Boris and Natasha on Rocky and Bullwinkle. “‘Get vurd to your president that ve vunt vay to back out of this vith honor. You agree take your nuclear missiles out of Turkey. You promise never to invade Kooba. Ve say okay and dismantle missiles in Kooba.’ And that, Sadie, is exactly what’s going to happen.”

She wasn’t giggling now. She was staring at me with huge saucer eyes. “You’re making this up to make me feel better.”

I said nothing.

“You’re not,” she whispered. “You really believe it.”

“Wrong,” I said. “I know it. Big difference.”

“George… nobody knows the future.”

“John Clayton claims to know, and you believe him. Roger from Yale claims to know, and you believe him, too.”

“You’re jealous of him, aren’t you?”

“You’re goddam right.”

“I never slept with him. I never even wanted to.” Solemnly, she added: “I could never sleep with a man who wears that much cologne.”

“Good to know. I’m still jealous.”

“Should I ask questions about how you—”

“No. I won’t answer them.” I probably shouldn’t have told her as much as I had, but I couldn’t stop myself. And in truth, I would do it again. “But I will tell you one other thing, and this you can check yourself in a couple of days. Adlai Stevenson and the Russian representative to the UN are going to face off in the General Assembly. Stevenson’s going to exhibit huge photos of the missile bases the Russians are building in Cuba, and ask the Russian guy to explain what the Russians said wasn’t there. The Russian guy is going to say something like, ‘You must vait, I cannot respond viddout full translation.’ And Stevenson, who knows the guy can speak perfect English, is going to say something that’ll wind up in the history books along with ‘don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.’ He’s going to tell the Russian guy he can wait until hell freezes over.”

She looked at me doubtfully, turned to the night table, saw the charred pack of Winstons sitting on top of a hill of crushed butts, and said: “I think I’m out of cigarettes.”

“You should be okay until morning,” I said dryly. “It looks to me like you front-loaded about a week’s supply.”

“George?” Her voice was very small, very timid. “Will you stay with me tonight?”

“My car’s parked in your—”

“If one of the neighborhood neb-noses says something, I’ll tell them you came to see me after the president’s speech and it wouldn’t start.”

Considering how the Sunliner was running these days, that was plausible. “Does your sudden concern for propriety mean you’ve stopped worrying about nuclear Armageddon?”

“I don’t know. I only know I don’t want to be alone. I’ll even make love with you if that will get you to stay, but I don’t think it would be much good for either of us. My head aches so badly.”

“You don’t have to make love to me, hon. It’s not a business deal.”

“I didn’t mean—”

“Hush. I’ll get the aspirin.”

“And look on top of the medicine cabinet, would you? Sometimes I leave a pack of cigarettes there.”

She had, but by the time she’d taken three puffs of the one I lit for her, she was wall-eyed and dozing. I took it from between her fingers and mashed it out on the lower slope of Mount Cancer. Then I took her in my arms and laid back on the pillows. We fell asleep that way.

10

When I woke to the first long light of dawn, the fly of my slacks was unzipped and a skillful hand was exploring inside my underwear. I turned to her. She was looking at me calmly. “The world is still here, George. And so are we. Come on. But be gentle. My head still aches.”

I was gentle, and I made it last. We made it last. At the end, she lifted her hips and dug into my shoulder blades. It was her oh dear, oh my God, oh sugar grip.

“Anything.” She was whispering, her breath in my ear making me shiver as I came. “You can be anything, do anything, just say you’ll stay. And that you still love me.”

“Sadie… I never stopped.”

11

We had breakfast in her kitchen before I went back to Dallas. I told her it really was Dallas now, and although I didn’t have a phone yet, I would give her the number as soon as I had one.

She nodded and picked at her eggs. “I meant what I said. I won’t ask any more questions about your business.”

“That’s best. Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

“Huh?”

“Never mind.”

“Just tell me again that you’re up to good rather than no good.”

“Yes,” I said. “I’m one of the good guys.”

“Will you be able to tell me someday?”

“I hope so,” I said. “Sadie, those pictures he sent—”

“I tore them up this morning. I don’t want to talk about them.”

“We don’t have to. But I need you to tell me that’s all the contact you’ve had with him. That he hasn’t been around.”

“He hasn’t been. And the postmark on the envelope was Savannah.”

I’d noticed that. But I’d also noticed the postmark was almost two months old.

“He’s not big on personal confrontation. He’s brave enough in his mind, but I think he’s a physical coward.”

That struck me as a good assessment; sending the pictures was textbook passive-aggressive behavior. Still, she had been sure Clayton wouldn’t find out where she was now living and teaching, and she’d been wrong about that. “The behavior of mentally unstable people is hard to predict, honey. If you saw him, you’d call the police, right?”

“Yes, George.” With a touch of her old impatience. “I need to ask you one question, then we won’t talk about this anymore until you’re ready. If you ever are.”

“Okay.” I tried to prepare an answer to the question I was sure would be coming: Are you from the future, George?

“It’s going to sound crazy.”

“It’s been a crazy night. Go ahead.”

“Are you…” She laughed, then started to gather the plates. She went to the sink with them, and with her back turned, she asked: “Are you human? Like, from planet Earth?”

I went to her, reached around to cup her breasts, and kissed the back of her neck. “Totally human.”

She turned. Her eyes were grave. “Can I ask another?”

I sighed. “Shoot.”

“I’ve got at least forty minutes before I have to dress for school. Do you happen to have another condom? I think I’ve discovered the cure for headaches.”

CHAPTER 20

1

So in the end it only took the threat of nuclear war to bring us back together—how romantic is that?

Okay, maybe not.

Deke Simmons, the sort of man who took an extra hankie to sad movies, approved heartily. Ellie Dockerty did not. Here is a strange thing I’ve noticed: women are better at keeping secrets, but men are more comfortable with them. A week or so after the Cuban Missile Crisis ended, Ellie called Sadie into her office and shut the door—not a good sign. She was typically blunt, asking Sadie if she knew any more about me than she had before.

“No,” Sadie said.

“But you’ve begun again.”

“Yes.”

“Do you even know where he lives?”

“No, but I have a telephone number.”

Ellie rolled her eyes, and who could blame her. “Has he told you anything at all about his past? Whether he’s been married before? Because I believe that he has been.”

Sadie stayed silent.

“Has he happened to mention if he’s left a dropped calf or two behind somewhere? Because sometimes men do that, and a man who’s done it once will not hesitate to—”

“Miz Ellie, may I go back to the library now? I’ve left a student in charge, and while Helen’s very responsible, I don’t like to leave them too—”

“Go, go.” Ellie flapped a hand at the door.

“I thought you liked George,” Sadie said as she got up.

“I do,” Ellie replied—in a tone, Sadie told me later, that said I did. “I’d like him even better—and like him for you better—if I knew what his real name was, and what he’s up to.”

“Don’t ask, don’t tell,” Sadie said as she went to the door.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“That I love him. That he saved my life. That all I have to give him in return is my trust, and I intend to give it.”

Miz Ellie was one of those women accustomed to getting the last word in most situations, but she didn’t get it that time.

2

We fell into a pattern that fall and winter. I would drive down to Jodie on Friday afternoons. Sometimes on the way, I would buy flowers at the florist in Round Hill. Sometimes I’d get my hair cut at the Jodie Barber Shop, which was a great place to catch up on all the local chatter. Also, I’d gotten used to having it short. I could remember wearing it so long it flopped in my eyes, but not why I’d put up with the annoyance. Getting used to Jockey shorts over boxers was harder, but after awhile my balls no longer claimed to be strangling.

We’d usually eat at Al’s Diner on those evenings, then go to the football game. And when the football season ended, there was basketball. Sometimes Deke joined us, decked out in his school sweater with Brian the Fightin’ Denton Lion on the front.

Miz Ellie, never.

Her disapproval did not stop us from going to the Candlewood Bungalows after the Friday games. I usually stayed there alone on Saturday nights, and on Sundays I’d join Sadie for services at Jodie’s First Methodist Church. We shared a hymnal and sang many verses of “Bringing in the Sheaves.” Sowing in the morning, sowing seeds of kindness… the melody and those well-meant sentiments still linger in my head.

After church we’d have the noon meal at her place, and after that I’d drive back to Dallas. Every time I made that drive, it seemed longer and I liked it less. Finally, on a chilly day in mid-December, my Ford threw a rod, as if expressing its own opinion that we were driving in the wrong direction. I wanted to get it fixed—that Sunliner convertible was the only car I ever truly loved—but the guy at Kileen Auto Repair told me it would take a whole new engine, and he just didn’t know where he could lay his paws on one.

I dug into my still-sturdy (well… relatively sturdy) cash reserve and bought a 1959 Chevy, the kind with the bodacious gull-wing tailfins. It was a good car, and Sadie said she absolutely adored it, but for me it was never quite the same.

We spent Christmas night together at the Candlewood. I put a sprig of holly on the dresser and gave her a cardigan. She gave me a pair of loafers that are on my feet now. Some things are meant to keep.

We had dinner at her house on Boxing Day, and while I was setting the table, Deke’s Ranch Wagon pulled into the driveway. That surprised me, because Sadie had said nothing about company. I was more surprised to see Miz Ellie on the passenger side. The way she stood with her arms folded, looking at my new car, told me I wasn’t the only one who’d been kept in the dark about the guest list. But—credit where credit is due—she greeted me with a fair imitation of warmth and kissed me on the cheek. She was wearing a knitted ski cap that made her look like an elderly child, and offered me a tight smile of thanks when I whisked it off her head.

“I didn’t get the memo, either,” I said.

Deke pumped my hand. “Merry Christmas, George. Glad to see you. Gosh, something smells good.”

He wandered off to the kitchen. A few moments later I heard Sadie laugh and say, “Get your fingers out of that, Deke, didn’t your mama raise you right?”

Ellie was slowly undoing the keg buttons of her coat, never taking her eyes from my face. “Is it wise, George?” she asked. “What you and Sadie are doing—is it wise?”

Before I could answer, Sadie swept in with the turkey she’d been fussing over ever since we’d gotten back from the Candlewood Bungalows. We sat down and linked hands. “Dear Lord, please bless this food to our bodies,” Sadie said, “and please bless our fellowship, one with the other, to our minds and our spirits.”

I started to let go, but she was still gripping my hand with her left and Ellie’s with her right. “And please bless George and Ellie with friendship. Help George remember her kindness, and help Ellie to remember that without George, there would be a girl from this town with a terribly scarred face. I love them both, and it’s sad to see mistrust in their eyes. For Jesus’s sake, amen.”

“Amen!” Deke said heartily. “Good prayer!” He winked at Ellie.

I think part of Ellie wanted to get up and leave. It might have been the reference to Bobbi Jill that stopped her. Or maybe it was how much she’d come to respect her new school librarian. Maybe it even had a little to do with me. I like to think so.

Sadie was looking at Miz Ellie with all her old anxiety.

“That turkey looks absolutely wonderful,” Ellie said, and handed me her plate. “Would you help me to a drumstick, George? And don’t spare the stuffing.”

Sadie could be vulnerable, and Sadie could be clumsy, but Sadie could also be very, very brave.

How I loved her.

3

Lee, Marina, and June went to the de Mohrenschildts’ to see in the new year. I was left to my own lonely devices, but when Sadie called and asked if I’d take her to the New Year’s Eve dance at Jodie’s Bountiful Grange, I hesitated.

“I know what you’re thinking,” she said, “but this will be better than last year. We’ll make it better, George.”

So there we were at eight o’clock, once more dancing beneath sagging nets of balloons. This year’s band was called the Dominoes. They featured a four-man horn section instead of the Dick Dale—style surf guitars that had dominated the previous year’s dance, but they also knew how to lay it down. There were the same two bowls of pink lemonade and ginger ale, one soft and one spiked. There were the same smokers clustered beneath the fire escape in the chill air. But it was better than last year. There was a great sense of relief and happiness. The world had passed under a nuclear shadow in October… but then it had passed back out again. I heard several approving comments about how Kennedy had made the bad old Russian bear back down.

Around nine o’clock, during a slow dance, Sadie suddenly screamed and broke away from me. I was sure she’d spotted John Clayton, and my heart jumped into my throat. But that had been a scream of pure happiness, because the two newcomers she had spotted were Mike Coslaw—looking absurdly handsome in a tweed topcoat—and Bobbi Jill Allnut. Sadie ran to them… and tripped over someone’s foot. Mike caught her and swung her around. Bobbi Jill waved to me, a little shyly.

I shook Mike’s hand and kissed Bobbi Jill on the cheek. The disfiguring scar was now a faint pink line. “Doctor says it’ll be all gone by next summer,” she said. “He called me his fastest-healing patient. Thanks to you.”

“I got a part in Death of a Salesman, Mr. A.,” Mike said. “I’m playing Biff.”

“Type-casting,” I said. “Just watch out for flying pies.”

I saw him talking to the band’s lead singer during one of the breaks, and knew perfectly well what was coming. When they got back on the stand, the singer said: “I’ve got a special request. Do we have a George Amberson and Sadie Dunhill in the house? George and Sadie? Come on up here, George and Sadie, outta your seats and onto your feets.”

We walked toward the bandstand through a storm of applause. Sadie was laughing and blushing. She shook her fist at Mike. He grinned. The boy was leaving his face; the man was coming in. A little shyly, but coming. The singer counted off, and the brass section swung into that downbeat I still hear in my dreams.

Bah-dah-dah… bah-dah-da-dee-dum…

I held my hands out to her. She shook her head, but began to swing her hips a little just the same.

“Go get him, Miz Sadie!” Bobbi Jill shouted. “Do the thing!”

The crowd joined in. “Go! Go! Go!”

She gave in and took my hands. We danced.

4

At midnight, the band played “Auld Lang Syne”—different arrangement from last year, same sweet song—and the balloons came drifting down. All around us, couples were kissing and embracing. We did the same.

“Happy New Year, G—” She pulled back from me, frowning. “What’s wrong?”

I’d had a sudden image of the Texas School Book Depository, an ugly brick square with windows like eyes. This was the year it would become an American icon.

It won’t. I’ll never let you get that far, Lee. You’ll never be in that sixth-floor window. That’s my promise.

“George?”

“Goose walked over my grave, I guess,” I said. “Happy New Year.”

I went to kiss her, but she held me back for a moment. “It’s almost here, isn’t it? What you came to do.”

“Yes,” I said. “But it’s not tonight. For tonight it’s just us. So kiss me, honey. And dance with me.”

5

I had two lives in late 1962 and early 1963. The good one was in Jodie, and at the Candlewood in Kileen. The other was in Dallas.

Lee and Marina got back together. Their first stop in Dallas was a dump just around the corner from West Neely. De Mohrenschildt helped them move in. George Bouhe wasn’t in evidence. Neither were any of the other Russian migrs. Lee had driven them away. They hated him, Al had written in his notes, and below that: He wanted them to.

The crumbling redbrick at 604 Elsbeth Street had been divided into four or five apartments bursting with poor folks who worked hard, drank hard, and produced hordes of snot-nosed yelling kids. The place actually made the Oswalds’ Fort Worth domicile look good.

I didn’t need electronic assistance to monitor the deteriorating condition of their marriage; Marina continued to wear shorts even after the weather turned cool, as if to taunt him with her bruises. And her sex appeal, of course. June usually sat between them in her stroller. She no longer cried much during their shouting matches, only watched, sucking her thumb or a pacifier.

One day in November of 1962, I came back from the library and observed Lee and Marina on the corner of West Neely and Elsbeth, shouting at each other. Several people (mostly women at that hour of the day) had come out on their porches to watch. June sat in the stroller wrapped in a fuzzy pink blanket, silent and forgotten.

They were arguing in Russian, but the latest bone of contention was clear enough from Lee’s jabbing finger. She was wearing a straight black skirt—I don’t know if they were called pencil skirts back then or not—and the zipper on her left hip was halfway down. Probably it just snagged in the cloth, but listening to him rave, you would’ve thought she was trolling for men.

She brushed back her hair, pointed at June, then waved a hand at the house they were now inhabiting—the broken gutters dripping black water, the trash and beer cans on the bald front lawn—and screamed at him in English: “You say happy lies, then bring wife and baby to this peegsty!”

He flushed all the way to his hairline and clutched his arms across his thin chest, as if to anchor his hands and keep them from doing damage. He might have succeeded—that time, at least—if she hadn’t laughed, then twirled one finger around her ear in a gesture that must be common to all cultures. She started to turn away. He hauled her back, bumping the stroller and almost overturning it. Then he slugged her. She fell down on the cracked sidewalk and covered her face when he bent over her. “No, Lee, no! No more heet me!”

He didn’t hit her. He yanked her to her feet and shook her, instead. Her head snapped and rolled.

“You!” a rusty voice said from my left. It made me jump. “You, boy!”

It was an elderly woman on a walker. She was standing on her porch in a pink flannel nightgown with a quilted jacket over it. Her graying hair stood straight up, making me think of Elsa Lanchester’s twenty-thousand-volt home permanent in The Bride of Frankenstein.

“That man is beating on that woman! Go down there and put a stop to it!”

“No, ma’am,” I said. My voice was unsteady. I thought of adding I won’t come between a man and his wife, but that would have been a lie. The truth was that I wouldn’t do anything that might disturb the future.

“You coward,” she said.

Call the cops, I almost said, but bit it back just in time. If it wasn’t in the old lady’s head and I put it there, that could also change the course of the future. Did the cops come? Ever? Al’s notebook didn’t say. All I knew was that Oswald would never be jugged for spousal abuse. I suppose in that time and that place, few men were.

He was dragging her up the front walk with one hand and yanking the stroller with the other. The old woman gave me a final withering glance, then clumped back into her house. The other spectators were doing the same. Show over.

From my living room, I trained my binoculars on the redbrick monstrosity catercorner from me. Two hours later, just as I was about to give up the surveillance, Marina emerged with the small pink suitcase in one hand and the blanket-wrapped baby in the other. She had changed the offending skirt for slacks and what appeared to be two sweaters—the day had turned cold. She hurried down the street, several times looking back over her shoulder for Lee. When I was sure he wasn’t going to follow her, I did.

She went as far as Mister Car Wash four blocks down West Davis, and used the pay telephone there. I sat across the street at the bus stop with a newspaper spread out in front of me. Twenty minutes later, trusty old George Bouhe showed up. She spoke to him earnestly. He led her around to the passenger side of the car and opened the door for her. She smiled and pecked him on the corner of the mouth. I’m sure he treasured both. Then he got in behind the wheel and they drove away.

6

That night there was another argument in front of the Elsbeth Street house, and once again most of the immediate neighborhood turned out to watch. Feeling there was safety in numbers, I joined them.

Someone—almost certainly Bouhe—had sent George and Jeanne de Mohrenschildt to get the rest of Marina’s things. Bouhe probably figured they were the only ones who’d be able to get in without physical restraints being imposed on Lee.

“Be damned if I’ll hand anything over!” Lee shouted, oblivious of the rapt neighbors taking in every word. Cords stood out on his neck; his face was once more a bright, steaming red. How he must have hated that tendency to blush like a lttle girl who’s been caught passing love-notes.

De Mohrenschildt took the reasonable approach. “Think, my friend. This way there’s still a chance. If she sends the police…” He gave a shrug and lifted his hands to the sky.

“Give me an hour, then,” Lee said. He was showing teeth, but that expression was the farthest thing in the world from a smile. “It’ll give me a chance to put a knife through ever one of her dresses and break ever one of the toys those fatcats sent to buy my daughter.”

“What’s going on?” a young man asked me. He was about twenty, and had pulled up on a Schwinn.

“Domestic argument, I guess.”

“Osmont, or whatever his name is, right? Russian lady left him? About time, I’d say. That guy there’s crazy. He’s a commie, you know it?”

“I think I heard something about that.”

Lee was marching up the porch steps with his head back and his spine straight—Napoleon retreating from Moscow—when Jeanne de Mohrenschildt called to him sharply. “Stop it, you stupidnik!”

Lee turned to her, his eyes wide, unbelieving… and hurt. He looked at de Mohrenschildt, his expression saying can’t you control your wife, but de Mohrenschildt said nothing. He looked amused. Like a jaded theatergoer watching a play that’s actually not too bad. Not great, not Shakespeare, but a perfectly acceptable time-passer.

Jeanne: “If you love your wife, Lee, for God’s sake stop acting like a spoiled brat. Behave.”

“You can’t talk to me like that.” Under stress, his Southern accent grew stronger. Can’t became cain’t; like that became like-at.

“I can, I will, I do,” she said. “Let us get her things, or I’ll call the police myself.”

Lee said, “Tell her to shut up and mind her business, George.”

De Mohrenschildt laughed cheerily. “Today you are our business, Lee.” Then he grew serious. “I am losing respect for you, Comrade. Let us in now. If you value my friendship as I value yours, let us in now.”