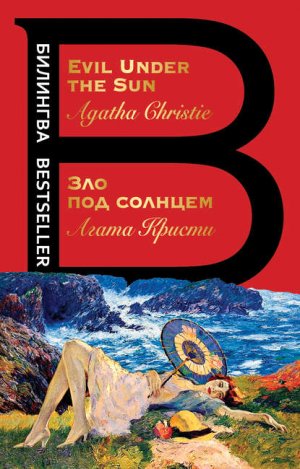

«ло под солнцем / Evil Under the Sun ристи јгата

ќна услышала, как ѕатрик –едферн шумно вздохнул, затем его голос наполнилс€ плохо сдерживаемой €ростью:

Ц†√осподи, если б этот гнусный изверг попалс€ ко мне в руки!..

ћисс Ѕрюстер поежилась. ¬оображение нарисовало убийцу, притаившегос€ за скалой. «атем она, оп€ть словно со стороны, услышала собственный голос:

Ц†“от, кто это сделал, вр€д ли стал здесь задерживатьс€. ћы должны вызвать полицию. ЌаверноеЕ†Ц она заколебалась,†Ц наверное, одному из нас следует остатьс€ сЕ с телом.

Ц†я останусь,†Ц вызвалс€ ѕатрик.

Ёмили облегченно вздохнула. ќна была не из тех, кто признаетс€ в собственном страхе, и все же втайне порадовалась тому, что ей не придетс€ остатьс€ здесь одной, где поблизости, возможно, разгуливает кровожадный мань€к.

Ц†’орошо,†Ц сказала она.†Ц я обернусь как можно быстрее. ¬озьму лодку, от лестницы у мен€ голова кружитс€. ¬†Ћезеркомб-Ѕэй есть констебль.

Ц†ƒа, да, как вы считаете нужным,†Ц механически пробормотал –едферн.

”силенно греб€ от берега, Ёмили увидела, как ѕатрик упал на колени перед мертвой женщиной и закрыл лицо руками. ¬ его поведении было что-то такое жалкое, что она помимо воли прониклась сочувствием к нему. ќн был похож на преданную собаку, стерегущую своего мертвого хоз€ина. » все же здравый смысл подсказывал ей: Ђƒл€ него самого и его жены это лучшее, что только могло произойти,†Ц как и дл€ ћаршалла и девочки. Ќо он вр€д ли способен увидеть все в таком свете, бедн€га!ї

Ёмили Ѕрюстер была из тех, кто не тер€ет голову в любой ситуации.

Chapter 5

Inspector Colgate stood back by the cliff waiting for the police surgeon to finish with ArlenaТs body. Patrick Redfern and Emily Brewster stood a little to one side.

Dr Neasdon rose from his knees with a quick deft movement. He said:

УStrangled Ц and by a pretty powerful pair of hands. She doesnТt seem to have put up much of a struggle. Taken by surprise. HТm Ц well Ц nasty business.Ф

Emily Brewster had taken one look and then quickly averted her eyes from the dead womanТs face. That horrible purple convulsed countenance. Inspector Colgate asked:

УWhat about time of death?Ф

Neasdon said irritably: УCanТt say definitely without knowing more about her. Lots of factors to take into account. LetТs see, itТs quarter to one now. What time was it when you found her?Ф

Patrick Redfern, to whom the question was addressed, said vaguely:

УSome time before twelve. I†donТt know exactly.Ф

Emily Brewster said: УIt was exactly a quarter to twelve when we found she was dead.Ф

УAh, and you came here in the boat. What time was it when you caught sight of her lying here?Ф

Emily Brewster considered.

УI†should say we rounded the point about five or six minutes earlier.Ф She turned to Redfern. УDo you agree?Ф

He said vaguely: УYes Ц yes Ц about that, I†should think.Ф

Neasdon asked the Inspector in a low voice: УThis the husband? Oh! I†see, my mistake. Thought it might be. He seems rather done in over it.Ф He raised his voice officially. УLetТs put it at twenty minutes to twelve. She cannot have been killed very long before that. Say between then and eleven Ц quarter to eleven at the earliest outside limit.Ф

The Inspector shut his notebook with a snap.

УThanks,Ф he said. УThat ought to help us considerably. Puts it within very narrow limits Ц less than an hour all told.Ф

He turned to Miss Brewster.

УNow then, I†think itТs all clear so far. YouТre Miss Emily Brewster and this is Mr Patrick Redfern, both staying at the Jolly Roger Hotel. You identify this lady as a fellow guest of yours at the hotel Ц the wife of Captain Marshall?Ф

Emily Brewster nodded.

УThen, I†think,Ф said Inspector Colgate, Уthat weТll adjourn to the hotel.Ф He beckoned to a constable. УHawkes, you stay here and donТt allow any one onto this cove. IТll be sending Phillips along later.Ф

УUpon my soul!Ф said Colonel Weston. УThis is a surprise finding you here!Ф

Hercule Poirot replied to the Chief ConstableТs greeting in a suitable manner. He murmured:

УAh, yes, many years have passed since that affair at St Loo.Ф

УI†havenТt forgotten it, though,Ф said Weston. УBiggest surprise of my life. The thing IТve never got over, though, is the way you got round me about that funeral business. Absolutely unorthodox, the whole thing. Fantastic!Ф

УTout de mme, mon Colonel,Ф said Poirot. УIt produced the goods, did it not?Ф

УEr Ц well, possibly. I†daresay we should have got there by more orthodox methods.Ф

УIt is possible,Ф agreed Poirot diplomatically.

УAnd here you are in the thick of another murder,Ф said the Chief Constable. УAny ideas about this one?Ф

Poirot said slowly: УNothing definite Ц but it is interesting.Ф

УGoing to give us a hand?Ф

УYou would permit it, yes?Ф

УMy dear fellow, delighted to have you. DonТt know enough yet to decide whether itТs a case for Scotland Yard or not. Offhand it looks as though our murderer must be pretty well within a limited radius. On the other hand, all these people are strangers down here. To find out about them and their motives youТve got to go to London.Ф

Poirot said: УYes, that is true.Ф

УFirst of all,Ф said Weston, УweТve got to find out who last saw the dead woman alive. Chambermaid took her breakfast at nine. Girl in the bureau downstairs saw her pass through the lounge and go out about ten.Ф

УMy friend,Ф said Poirot, УI†suspect that I†am the man you want.Ф

УYou saw her this morning? What time?Ф

УAt five minutes past ten. I†assisted her to launch her float from the bathing beach.Ф

УAnd she went off on it?Ф

УYes.Ф

УAlone?Ф

УYes.Ф

УDid you see which direction she took?Ф

УShe paddled round that point there to the right.Ф

УIn the direction of PixyТs Cove, that is?Ф

УYes.Ф

УAnd the time then was Ц Ф

УI†should say she actually left the beach at a quarter past ten.Ф

Weston considered.

УThat fits in well enough. How long should you say that it would take her to paddle round to the Cove?Ф

УAh, me, I†am not an expert. I†do not go in boats or expose myself on floats. Perhaps half an hour?Ф

УThatТs about what I†think,Ф said the Colonel. УShe wouldnТt be hurrying, I†presume. Well, if she arrived there at a quarter to eleven, that fits in well enough.Ф

УAt what time does your doctor suggest she died?Ф

УOh, Neasdon doesnТt commit himself. HeТs a cautious chap. A†quarter to eleven is his earliest outside limit.Ф

Poirot nodded.

He said: УThere is one other point that I†must mention. As she left Mrs Marshall asked me not to say I†had seen her.Ф

Weston stared. He said:

УHТm, thatТs rather suggestive, isnТt it?Ф

Poirot murmured: УYes, I†thought so myself.Ф

Weston tugged at his moustache. He said:

УLook here, Poirot. YouТre a man of the world. What sort of a woman was Mrs Marshall?Ф

A†faint smile came to PoirotТs lips.

He asked: УHave you not already heard?Ф

The Chief Constable said drily:

УI†know what the women say of her. They would. How much truth is there in it? Was she having an affair with this fellow Redfern?Ф

УI†should say undoubtedly yes.Ф

УHe followed her down here, eh?Ф

УThere is reason to suppose so.Ф

УAnd the husband? Did he know about it? What did he feel?Ф

Poirot said slowly: УIt is not easy to know what Captain Marshall feels or thinks. He is a man who does not display his emotions.Ф

Weston said sharply: УBut he might have Сem, all the same.Ф

Poirot nodded. He said:

УOh, yes, he might have them.Ф

The Chief Constable was being as tactful as it was in his nature to be with Mrs Castle.

Mrs Castle was the owner and proprietress of the Jolly Roger Hotel. She was a woman of forty odd with a large bust, rather violent henna-red hair, and an almost offensively refined manner of speech. She was saying:

УThat such a thing should happen in my Hotel! Ay am sure it has always been the quayettest place imaginable! The people who come here are such nice people. No rowdiness Ц if you know what Ay mean. Not like the big hotels in St Loo.Ф

УQuite so, Mrs Castle,Ф said Colonel Weston. УBut accidents happen in the best-regulated Ц er Ц households.Ф

УAyТm sure Inspector Colgate will bear me out,Ф said Mrs Castle, sending an appealing glance towards the Inspector who was sitting looking very official. УAs to the laycensing laws. Ay am most particular. There has never been any irregularity!Ф

УQuite, quite,Ф said Weston. УWeТre not blaming you in any way, Mrs Castle.Ф

УBut it does so reflect upon an establishment,Ф said Mrs Castle, her large bust heaving. УWhen Ay think of the noisy gaping crowds. Of course no one but hotel guests are allowed upon the island Ц but all the same they will no doubt come and point from the shore.Ф

She shuddered.

Inspector Colgate saw his chance to turn the conversation to good account. He said:

УIn regard to that point youТve just raised. Access to the island. How do you keep people off?Ф

УAy am most particular about it.Ф

УYes, but what measures do you take? What keeps Сem off? Holiday crowds in summer-time swarm everywhere like flies.Ф

Mrs Castle shuddered slightly again. She said:

УThat is the fault of the charabancs. Ay have seen eighteen at one time parked by the quay at Leathercombe Bay. Eighteen!Ф

УJust so. How do you stop them coming here?Ф

УThere are notices. And then, of course, at high tide, we are cut off.Ф

УYes, but at low tide?Ф

Mrs Castle explained. At the island end of the causeway there was a gate. This said, УJolly Roger Hotel. Private. No entry except to Hotel.Ф The rocks rose sheer out of the sea on either side there and could not be climbed.

УAny one could take a boat, though, I†suppose, and row round and land on one of the coves? You couldnТt stop them doing that. ThereТs a right of access to the foreshore. You canТt stop people being on the between low and high waermark.Ф

But this, it seemed, very seldom happened. Boats could be obtained at Leathercombe Bay harbour but from there it was a long row to the island and there was also a strong current just outside Leathercombe Bay harbour. There were notices, too, on both Gull Cove and Pixy Cove by the ladder. She added that George or William was always on the lookout at the bathing beach proper which was the nearest to the mainland.

УWho are George and William?Ф

УGeorge attends to the bathing beach. He sees to the costumes and the floats. William is the gardener. He keeps the paths and marks the tennis courts and all that.Ф

Colonel Weston said impatiently: УWell, that seems clear enough. ThatТs not to say that nobody could have come from outside, but anyone who did so took a risk Ц the risk of being noticed. WeТll have a word with George and William presently.Ф

Mrs Castle said: УAy do not care for trippers Ц a very noisy crowd and they frequently leave orange peel and cigarette boxes on the causeway and down by the rocks, but all the same Ay never thought one of them would turn out to be a murderer. Oh, dear! It really is too terrible for words. A†lady like Mrs Marshall murdered and whatТs so horrible, actually Ц er Ц strangledЕФ

Mrs Castle could hardly bring herself to say the word. She brought it out with the utmost reluctance.

Inspector Colgate said soothingly: УYes, itТs a nasty business.Ф

УAnd the newspapers. My hotel in the newspapers!Ф

Colgate said, with a faint grin: УOh, well, itТs advertisement, in a way.Ф

Mrs Castle drew herself up. Her bust heaved and whale-bone creaked. She said icily:

УThat is not the kind of advertisement Ay care about, Mr Colgate.Ф

Colonel Weston broke in. He said:

УNow then, Mrs Castle, youТve got a list of the guests staying here, as I†asked you?Ф

УYes, sir.Ф

Colonel Weston pored over the hotel register. He looked over to Poirot who made the forth member of the group assembled in the ManageressТs office.

УThis is where youТll probably be able to help us presently.Ф He read down the names. УWhat about servants?Ф

Mrs Castle produced a second list.

УThere are four chambermaids, the head waiter and three under him and Henry in the bar. William does the boots and shoes. Then thereТs the cook and two under her.Ф

УWhat about the waiters?Ф

УWell, sir, Albert, the Mater Dotel, came to me from the Vincent at Plymouth. He was there for some years. The three under him have been here for three years Ц one of them four. They are very nice lads and most respectable. Henry has been here since the hotel opened. He is quite an institution.Ф

Weston nodded.

He said to Colgate: УSeems all right. YouТll check up on them, of course. Thank you, Mrs Castle.Ф

УThat will be all you require?Ф

УFor the moment, yes.Ф

Mrs Castle creaked out of the room.

Weston said: УFirst thing to do is to talk with Captain Marshall.Ф

Kenneth Marshall sat quietly answering the questions put to him. Apart from a slight hardening of his features he was quite calm. Seen here, with the sunlight falling on him from the window, you realized that he was a handsome man. Those straight features, the steady blue eyes, the firm mouth. His voice was low and pleasant. Colonel Weston was saying:

УI†quite understand, Captain Marshall, what a terrible shock this must be to you. But you realize that I†am anxious to get the fullest information as soon as possible.Ф

Marshall nodded.

He said: УI†quite understand. Carry on.Ф

УMrs Marshall was your second wife?Ф

УYes.Ф

УAnd you have been married, how long?Ф

УJust over four years.Ф

УAnd her name before she was married?Ф

УHelen Stuart. Her acting name was Arlena Stuart.Ф

УShe was an actress?Ф

УShe appeared in Revue and musical shows.Ф

УDid she give up the stage on her marriage?Ф

УNo. She continued to appear. She actually retired only about a year and a half ago.Ф

УWas there any special reason for her retirement?Ф

Kenneth Marshall appeared to consider.

УNo,Ф he said. УShe simply said that she was tired of it all.Ф

УIt was not Ц er Ц in obedience to your special wish?Ф

Marshall raised his eyebrows.

УOh, no.Ф

УYou were quite content for her to continue acting after your marriage?Ф

Marshall smiled very faintly.

УI†should have preferred her to give it up Ц that, yes. But I†made no fuss about it.Ф

УIt caused no point of dissension between you?Ф

УCertainly not. My wife was free to please herself.Ф

УAnd Ц the marriage was a happy one?Ф

Kenneth Marshall said coldly: УCertainly.Ф

Colonel Weston paused a minute.

Then he said: УCaptain Marshall, have you any idea who could possibly have killed your wife?Ф

The answer came without the least hesitation.

УNone whatsoever.Ф

УHad she any enemies?Ф

УPossibly.Ф

УAh?Ф

The other went on quickly. He said: УDonТt misunderstand me, sir. My wife was an actress. She was also a very good-looking woman. In both capacities she aroused a certain amount of envy and jealousy. There were fusses over parts Ц there was rivalry from other women Ц there was a good deal, shall we say, of general envy, hatred, malice, and all uncharitableness! But that is not to say that there was any one who was capable of deliberately murdering her.Ф

Hercule Poirot spoke for the first time. He said:

УWhat you really mean. Monsieur, is that her enemies were mostly, or entirely, women?Ф

Kenneth Marshall looked across at him.

УYes,Ф he said. УThat is so.Ф

The Chief Constable said: УYou know of no man who had a grudge against her?Ф

УNo.Ф

УWas she previously acquainted with anyone in this hotel?Ф

УI†believe she had met Mr Redfern before Ц at some cocktail party. Nobody else to my knowledge.Ф

Weston paused. He seemed to deliberate as to whether to pursue the subject. Then he decided against that course. He said:

УWe now come to this morning. When was the last time you saw your wife?Ф

Marshall paused a minute, then he said:

УI†looked in on my way down to breakfast Ц Ф

УExcuse me, you occupied separate rooms?Ф

УYes.Ф

УAnd what time was that?Ф

УIt must have been about nine oТclock.Ф

УWhat was she doing?Ф

УShe was opening her letters.Ф

УDid she say anything?Ф

УNothing of any particular interest. Just good-morning Ц and that it was a nice day Ц that sort of thing.Ф

УWhat was her manner? Unusual at all?Ф

УNo, perfectly normal.Ф

УShe did not seem excited, or depressed, or upset in any way?Ф

УI†certainly didnТt notice it.Ф

Hercule Poirot said: УDid she mention at all what were the contents of her letters?Ф

Again a faint smile appeared on MarshallТs lips. He said:

УAs far as I†can remember, she said they were all bills.Ф

УYour wife breakfasted in bed?Ф

УYes.Ф

УDid she always do that?Ф

УInvariably.Ф

Hercule Poirot said: УWhat time did she usually come downstairs?Ф

УOh! between ten and eleven Ц usually nearer eleven.Ф

Poirot went on: УIf she were to descend at ten oТclock exactly, that would be rather surprising?Ф

УYes. She wasnТt often down as early as that.Ф

УBut she was this morning. Why do you think that was, Captain Marshall?Ф

Marshall said unemotionally: УHavenТt the least idea. Might have been the weather Ц extra fine day and all that.Ф